Am I staring at you because yours is the only unmasked face? Your blank eyes stare back so neutrally that I in turn feel void. There is no threat in this stare and no invitation. At first you are empty, without signification. We share the stare from the sidewalk, until I realise I am staring at someone’s house, someone’s property, I am drawing attention to myself, I move on.

*

After losing my job in your home state of Tasmania, I return to Victoria. Fired because of a plague. As the week goes on, the levels of infections rise globally. After the state government announces a lockdown, we decide that I will stay with you in the West Melbourne terrace house you rent with two friends.

Between 1850 to 1890, large numbers of terrace houses like yours were built in the inner city suburbs in the colonial metropoles of Sydney, Hobart and Melbourne. Often designed to be mass-produced in groupings of two to half-a-dozen houses, these 19th century inner city worker and middle-class houses still make up a decent portion of Melbourne’s oldest inner-suburbs.

*

The Edwardian and Victorian terrace house, along with other imported architectural reproductions, are envoys of an offshore European past. They are synonymous with the urban housing of a colony generating fast wealth off the back of Indigenous dispossession.

The 19th century story of housing for the First Nations people who had been living uninterrupted on their ancestral Country Narrm/Birrarung-ga – labelled first as ‘Port Phillip Bay’ and later ‘Melbourne’ – is marked by inhumane brutality. Like my own ancestral people in lutruwita/Tasmania, First Nations families were forced to flee their homeland in order to survive the British colonists’ Frontier violence.

Beyond the rare case of (often illegal or inequitable) land agreements, the threat of rape and murder moved people to the partial and unstable safety of church missions and later state-run reserves, away from the growing metropolis of Melbourne. Each mission site has its own stories to tell. The accounts of First Nations’ people who stayed or were drawn to the city are more difficult to trace, or are kept tight in family lines.

In the early period of isolation, I choose to further isolate myself: disconnect from Instagram, hardly reply to texts from friends. Words and images are viral enough. I can only seem to savour the digital ghost of my family, video-calling from interstate. In calling, I feel green: fern fronds, sea lettuce, infinite moss. Reminders I don’t belong in the city.

As Tasmanians, we are taught to savour the isolation of a largely unpopulated island, to become in the white noise of roaring forties winds, to blow back into nature. Isolation ‘down there’ is a melancholic, romantic comfort that city isolation reminds me I took for granted as a kid. On the mainland, living in Kulin country in Melbourne, you get the feeling isolation makes cities dysfunctional. Were we or were we not supposed to be walking and talking over the top of each other, just as it was? Is there a different way for a city to be? The intimidation of empty spaces and unoccupied streets is lessened by the growing sounds of native birds. How to know if they were always there. And who else? Walking to and from the market, the oval, the coffee shop, I begin to see you everywhere. I tell my partner. Orbish eyes look back at us. Who are you and why are you here?

*

Victorian architecture reveals the fragile legitimisation of second generation settlers shrugging off their penal beginnings, with housing where exterior style trumps form and function. In ‘The Australian Ugliness’, Robin Boyd notes that in the 19th century, immigrants displayed new wealth through the decorative features of their homes. ‘On this self-conscious turn, the Van Deiman’s Land Monthly Magazine in November, 1835 noted “… This love of display, so inconsistent with the character and situation of settlers in a new country, may indeed have partly originated in each wishing to impress upon his neighbour a due sense of his previous circumstances”[1].

By May we would leave the house only for essential activities: exercise, food shopping, doctors appointments. Australia was ‘doing well’ but expected the number of cases to be devastatingly high unless we stepped away from each other. Each day you would point to a plastered figure of a woman’s face on the facade of so many terrace houses we passed.

“Who is she?” you asked me.

I called my friend living in Paris. He mused “Hestia, the goddess of the home?”

We impulsively asked everyone we spoke to, of all generations: “Do you know her?” “Some Greek or Roman thing,” we thought. “Must have a really old meaning”.

It turns out a ‘mascaron’ ornament is a face, usually human or a chimera, that was created architecturally in the Middle Ages. They are in the same family as a ‘grotesque’ or a ‘gargoyle’. The face’s original function was to scare away evil spirits and prevent them from entering a building. In the French Art Nouveau and Beaux Arts styles, function gave way to decoration. In the colonies such as so-called ‘Australia’, the European mascaron found itself looking out at stolen Indigenous land, harboring these new bad spirits within the mascaron’s own home.

*

Sometimes in the form of a wise, bearded man or plucky young voyager, these stoney men are trumped in popularity by the face of a calm, composed woman. She is neutral in appearance, except for the occasional addition of a cluster of 4 stars on her head. Her presence obscures a joint in the terrace’s basic structure, so she herself is a mask. The erection of the 19th century terrace house, complete with its mascaron frills, marked out a ‘new normal’ for urban domestic living in Victoria. The introduction of the mascaron, with her Athenian composition, configured the colony’s new domestic face – that of the placid white woman, whose stare looked anywhere but to the face of the Aboriginal woman, whose ‘new normal’ was now akin to nightmare.

Adam Phillips writes: “When I dream, I have taken myself to an unpredicted and unpredictable dramatic space, what Freud calls ‘the other scene’. While dreaming, I pay involuntary attention; on waking, it is as though I can choose what kind of attention I can give to my dream”. I am only half joking when I say I feel that we have entered the ‘other scene’. I have no sure way of believing the attention I first paid you was involuntary. I sleep and I sleep. I wake and I wake. Every day is 3pm, always far too soon.

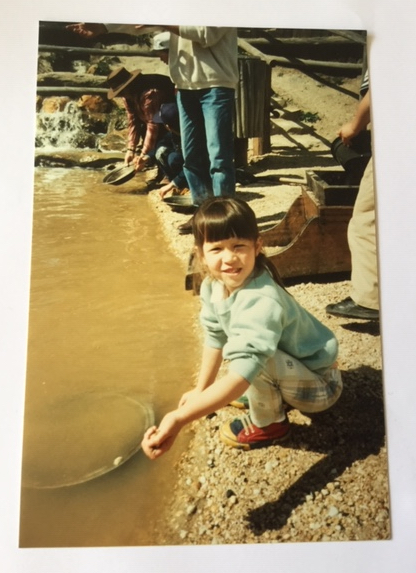

During this nebulous experience, national and state borders become tighter. Fear and paranoia rides high in private and public spaces. Around the globe, do-gooders and humorously spirited city officials put masks on state-commissioned statues to send the message home: wear your mask. People for the most part do, and at the same time, there is increased resentment towards some masked faces and not others. Back at the terrace house, my partner shows me a photo of her as a fresh-faced kid pretending to sift for treasure at the old goldfields, face smiling directly at the camera.

*

Terrace houses were built during a ‘boom’ period of wealth caused by the Gold Rush. The push to eject Chinese people from the young British colony came just as they arrived to work in the gold-fields. With legislation as early as the Chinese Immigration Act of 1855, the state of Victoria imposed crippling taxes exclusively on Chinese immigrants that enabled public-sanctioned racism and social segregation. From that point onwards, politicians and cartoonists helped fuel racism towards Asian people in general, leading the white imagination of ‘Australia’ towards the act of Federation in 1901. White Australia is an enduring, harmful construct that seeks to naturalise the white body as rightful possessor of the Australian landscape, denying the Aboriginal subject their history and degrading the non-Western immigrant. In 1970, my dad came to Narrm/Melbourne as a 17 year old Chinese-Malaysian student to study architecture on Wathaurong/Wadawarrung land. He arrived at the tail end of the White Australia policy in 1973, five years after First Nations Australians were given the right to vote. Here dad was culturally rejected by white society, and his trauma led him to be absent and present in my life. Stuck between his homeland and Australia, I was raised by my white mum.

Academic Ari Larissa Heinrich explains that the current COVID-19 Anti-Asian discrimination is historical. In the late 1800s, England and America were mischaracterising China as ‘The Sick Man of Asia’ directly due to misreporting that China was the “cradle of smallpox”[2] earlier in the century. Writer Cathy Park Hong describes how this current pandemic has ‘unmasked’ unsaid racism in America. Earlier in March in New York, Asian immigrants wore masks before the general populace. Being at the epicenter of pandemics like SARS, Asian people still remembered the seriousness and risks of transmissions; immigrants were being good public health citizens; they knew people could be asymptomatic and still spread the virus. Conversely, this brought Asian immigrants danger on the street as they became a visual link to the virus in the eyes of a xenophobe: ‘The masks depersonalised their faces, making the stereotypically “inscrutable” Asian face even more inscrutable’[3]. The ‘inscrutability’ of the Asian face in COVID-19 is met with suspicion and hostility, while the unimpassioned face of the white woman mascaron is an ode to classical beauty and to an ancient European past, projected onto the Australian mythscape by force.

Is she at all anxious as she witnesses many in West Melbourne walk east towards the Black Lives Matter[4] protest? Does she fear for her own #mustfall demise? From high upon the doorways of Parliament House, her mascaron cousins watch over the protest, 10,000 emboldened masked faces.

[1] Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness, 1961. FW. Cheshire, Melbourne, p.45.

[2] Before Coronovirus, China was falsely blamed for spreading smallpox. Racism played a role then, too., Ari Larissa Heinrich, The Conversation, 7 March 2020, https://theconversation.com/before-coronavirus-china-was-falsely-blamed-for-spreading-smallpox-racism-played-a-role-then-too-137884?fbclid=IwAR2bRHbqRynsYthgA-_fTdRCS8UqUjNXfCisUe7Qt6elezxHRsbDQm-dZUI, accessed 15/03/2020

[3] For a list of racially motivated attacks against Asian people in America, see The Slur I Never Expected To Hear, Cathy Park Hong, New York Times, 12th April 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/12/magazine/asian-american-discrimination-coronavirus.html, accessed 28/02/2020

[4] At the time of writing this, protests all over the US erupted in response to the brutal and avoidable murder of George Flloyd by Minneapolis Police. The Black Lives Matter protest in Narrm Melbourne on the 6/6/2020 was a show of solidarity and a protest against the ongoing emergency of Australian Indigenous deaths in custody.

Luxury Bunker is a series of texts presented by Contemporary Art Tasmania’s online platform for writing, Journal.

Traditionally Journal provides an opportunity for writers to respond to our gallery exhibitions. Due to the COVID -19 gallery closure we are expanding the scope of Journal and commissioning an international selection of writers to respond to their space, place, city… their bunker.